“Does not such a country, and such defenders of their country, deserve a song?”

At the western end of M St. overlooking the Potomac River is a small park that’s well-traveled by locals and Georgetown University students, but under-visited by the tourists that come to the District. Many know the name of Francis Scott Key, but few know the story behind the man or his memorial.

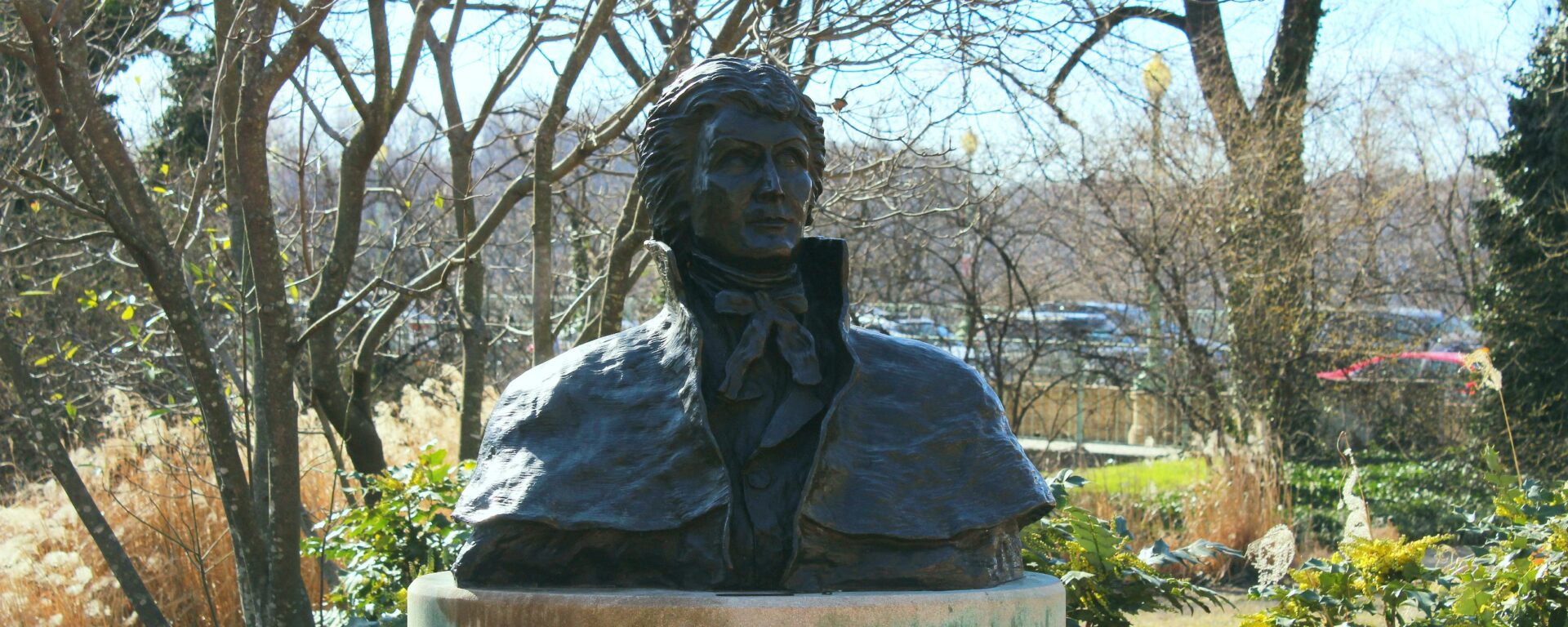

The $1.5 million park is on the same land where Key’s house once stood in Georgetown and sits next to the bridge that also bears his name. Two wisteria-covered pergolas encircle the stone-paved park and a low wall perfect for sitting surrounds it. There are signs around the park explaining Key’s life and the events surrounding his creation of his now-famous poem, “Defense of Fort M’Henry”, during the War of 1812. On the western edge is a bust of Francis Scott Key made by artist Betty Dunston. Behind it is a 60-foot flagpole flying the U.S. flag from 1814 (when Key witnessed the Battle of Baltimore, inspiring his poem) with 15 stars and 15 stripes. The park was designed by landscape architectural firm Oehme, van Sweden & Associates and opened in 1993. Their work on the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial and the World War II Memorial is their best known in D.C.

Today, Key is best known for writing the poem that would go on to become the national anthem more than 100 years after it was written. The inspiration for “Defense of Fort M’Henry” (now known as The Star-Spangled Banner) was the bombardment of Fort McHenry in the Battle of Baltimore. Key was aboard the HMS Tonnant to negotiate the release of American prisoners but was unable to leave since the British were about to begin their attack. The morning after the attack, Fort McHenry, undefeated, raised an American flag. Witnessing this scene, Key was inspired to write his poem.

During his life, Key was known less as a poet than as a lawyer. One of the early cases he worked on was the conspiracy trial of former Vice President Aaron Burr and Senator John Smith. He was the attorney for Sam Houston (who would go on to be the first president of Texas and, later, its governor) after Houston assaulted Ohio congressman William Stanbery with a hickory cane on Pennsylvania Ave. A few years later, Key was the prosecuting attorney against Richard Lawrence, the first person to attempt to assassinate a sitting president. Lawrence had approached President Andrew Jackson after a funeral with two pistols; both misfired, and Jackson proceeded to beat him with his cane until Lawrence was subdued.

Key’s legacy with slavery in early America is a complicated one. He purchased his first slave in his early 20s and represented slave owners seeking the return of their “property.” He also prosecuted cases against notable abolitionists of his time, accusing them of libel and of attempting to start slave rebellions. On the other hand, he also had a reputation as “The N***** Lawyer” since he would represent slaves seeking their freedom at no cost. He was a founding member of the American Colonization Society, which helped to create the African nation of Liberia by offering free African Americans the opportunity to return to Africa and establish a colony. He was even eulogized as a staunch anti-slavery advocate in newspaper editorials.

Key left a legacy beyond his contributions to the American identity. He was very devout and founded churches in the Washington, D.C. area. There are also many schools named after him in addition to memorials and bridges in D.C. and Maryland. The next time you hear the national anthem, take a moment to remember the life of Francis Scott Key.

Resources used for this article:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Scott_Key

https://www.nps.gov/places/francis-scott-key-memorial.htm

https://dcbikeblogger.wordpress.com/2014/10/14/francis-scott-key-park/